Kitchen sponges can be loaded with bacteria, but most of us prefer not to think about it. It’s scientists’ job to think about the things others don’t, however, and one team investigated sponges’ suitability as a microbial medium, learning that items intended for cleaning are actually a better home for microbial growth than instruments specifically designed for the purpose.

This could prove very useful, if you can get over how disgusting it is.

Laboratory efforts to grow bacteria usually focus on a single strain, hoping a plentiful supply of food and the right amount of warmth and light will do the trick. For some species, this is the case. Others, however, are the extroverts of the microworld, and do best when surrounded by a diverse array of other lifeforms.

“Bacteria are just like people living through the pandemic – some find it difficult being isolated while others thrive," Professor Lingchong You said in a statement. "We've demonstrated that in a complex community that has both positive and negative interactions between species, there is an intermediate amount of integration that will maximize its overall coexistence."

Soil suits both types of bacteria exceptionally well, which isn’t really surprising given the hundreds of millions of years they have had to not only adapt to it, but reshape it according to their needs. Plant roots and the human gut, both depending on healthy microbial communities, are similar to soil in providing spaces in a mix of sizes where bacteria can grow. Sponges, the team found, mimic that structure to a remarkable extent.

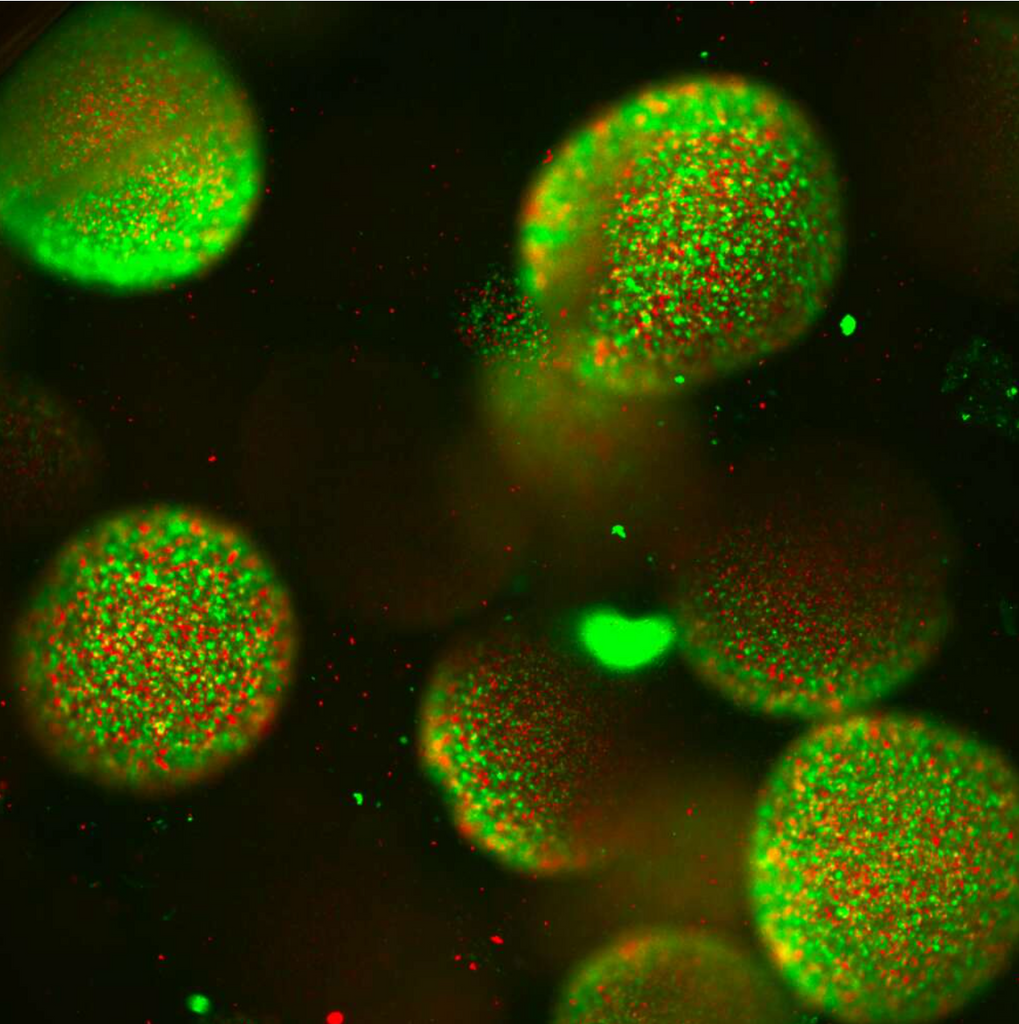

Researchers created a liquid medium containing many strains of E. coli and spread them over plates with growing spaces – or “wells” – of varying sizes. These ranged from six large wells where bacteria could congregate to 1,536 spaces so small a strain could expect to be alone. They found a Goldilocks zone of intermediate sizes maximized growth.

"The small portioning really hurt the species that depend on interactions with other species to survive, while the large portioning eliminated the members that suffer from these interactions (the loners)," Professor You said. "But the intermediate portioning allowed a maximum diversity of survivors in the microbial community."

Alongside the carefully designed growth media, the team performed the same experiment on strips of sponge and found the three-dimensional structure, designed for maximum water absorption, encouraged growth even better than ideally-sized wells.

"As it turns out, a sponge is a very simple way to implement multilevel portioning to enhance the overall microbial community," Professor You said.

The spaces are separate enough to allow bacteria that need to be alone to flourish, while still allowing successful strains to spread, at least while damp. Researchers struggling to culture truculent bacteria in the future might find this information useful, modifying the physical as well as chemical environment to enhance growth

Now if we can just work out how to clean our plates and cutlery with a petri dish maybe we won’t need to worry about eating off filthy items.

SpongeBath Solves The Germy Sponge Problem: https://www.spongebath.com/pages/sponge-bath-landing